I’m going to take you through the process of a graphic novel in a series of posts. This is from my perspective, as a writer and artist who makes fantasy books for middle grade and young adult readers - but hopefully it will be helpful even if you’re interested in making a different kind of book!

Taking about writing is easier than talking about art, for me, but I’m going to give it my best shot to talk about…

Finding your art style

Art style is one of those weird, slippery, hard-to-define things. I had one in high school (inspired by the illustrations in A Series of Unfortunate Events books, New Yorker cartoons, and Ghibli) and lost it when I went to art school. I tried a lot of different styles, took what I liked from each of them, and learned what I didn’t like. I also learned what was easy and hard for me to draw. This is all information that helps to inform your style! Ten years into making comics I feel pretty solid about my art style, but it’s been a constant evolution and I know it will continue to change.

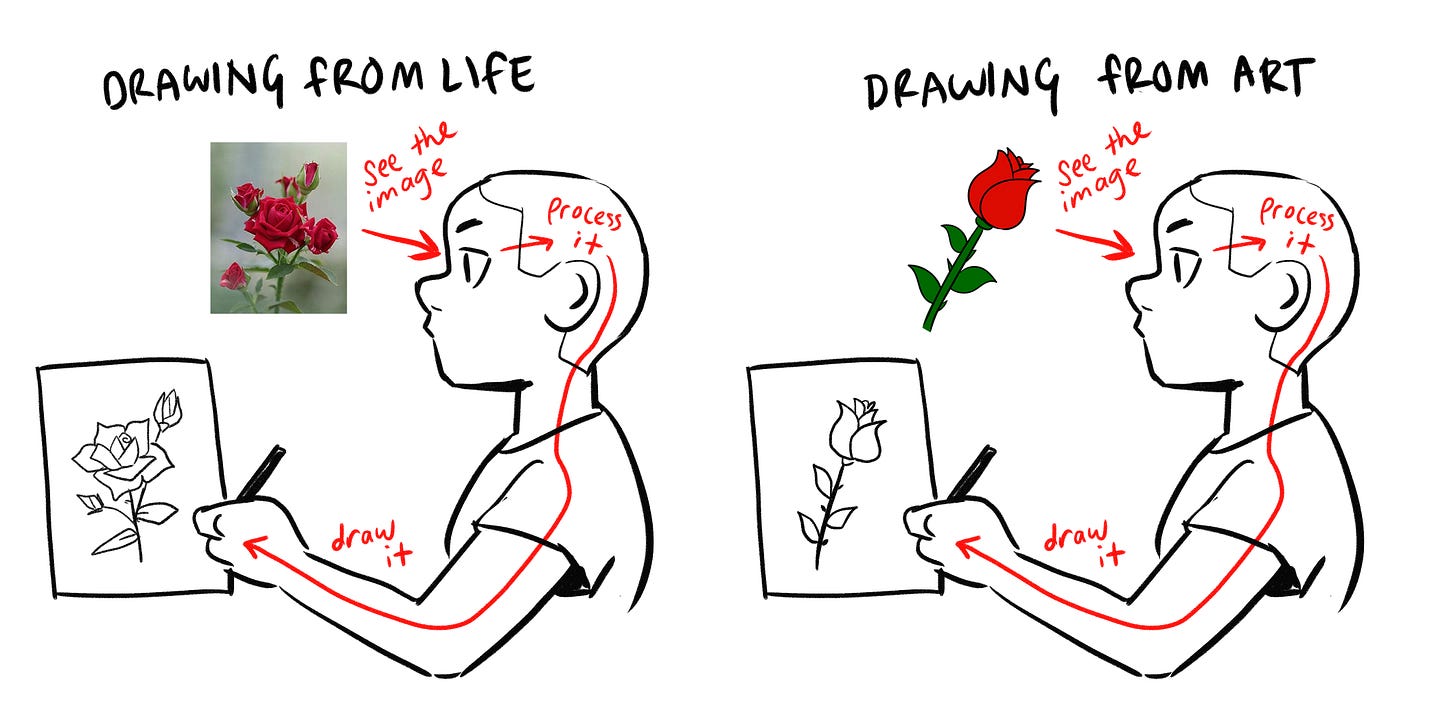

This is general drawing advice, more than graphic novel advice - but learn the fundamentals. It can feel easier to just copy a cartoon - to see how someone else has stylized real life, and borrow their shortcuts. But in my option, drawing from life and photographs will help you form your own, unique style. Art is the world processed through our minds, and every mind is unique. If you’re just copying the world processed through someone else’s mind, you’re accepting all the stylistic choices they made. It can be a good way to learn about those choices, but it’s not a replacement for drawing from life.

The diagram below illustrates it as best I can. The point isn’t that either drawing of a rose is better. The point is that the one drawn from life is more interesting and more unique to the artist.

Note: sometimes it is easier to copy from a cartoon! Sometimes there’s a car in one scene of your book and it’s not important and you don’t want to spend the time figuring out how to draw a car in your style, you just want it to read as a car. I think you CAN go to other artists and see how they stylized cars - copy their homework, so to speak. But for the subjects that you are interested in - people, animals, whatever the focus of your comic is - I really recommend working to develop your own way of drawing them. Once you have those fundamentals, you can and should look at other artists’ work and take inspiration from their individual styles.

Style takes a long time to develop, and is always changing. And the reason it’s so relevant to graphic novels is that style informs the story.

Examples

All art belongs to the respective creators and is only used as an example.

XKCD by Randall Munroe is a webcomic about, well, lots of things, but there are a ton of math and science jokes. The style looks like a diagram your high school physics teacher would scribble on the whiteboard to explain a concept. Each comic stands alone, rather than having ongoing narrative, so distinguishing the characters isn’t high priority. This allows the figures to be highly simple and iconic. The art is a vessel for the more complicated words.

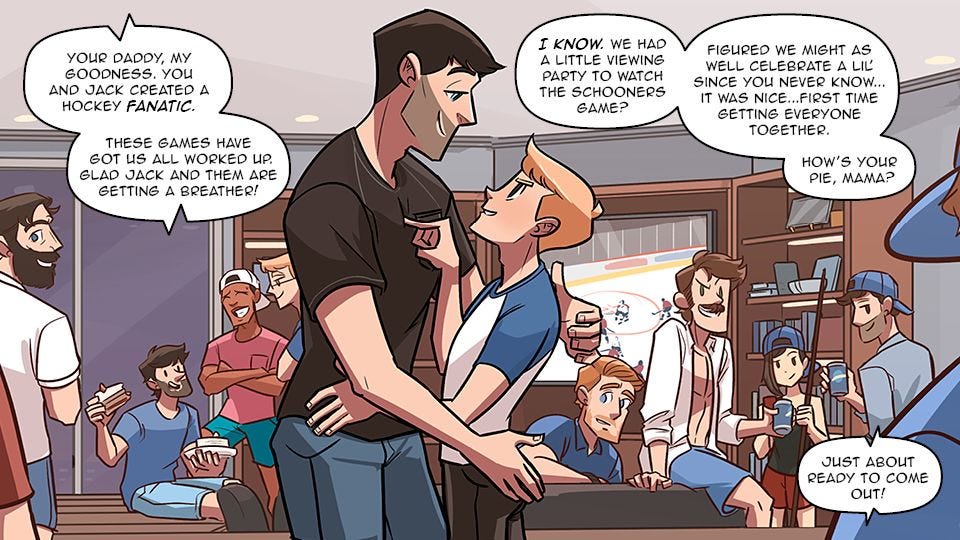

Check, Please by Ngozi Ukazu is a longform narrative with romance, friendship, action, and jokes. The characters are easy to distinguish from one another. They have fairly realistic proportions, which lends itself to the sports-action side of the comic and the romance. They have big eyes and simple, expressive faces, which lends itself to the emotions and drama. The whole style is bouncy, fun, and character-focused.

Delicious in Dungeon, or Dungeon Meshi, by Ryoko Kui is a manga about a D&D-esque adventuring party exploring a dungeon and eating monsters. The characters are fun, but the comic is focused on the interesting world they’re exploring. Ryoko Kui gets very into the mechanics of magic in this world, and to do that well, you need a world that feels SOLID. She renders the monsters and settings with a lot of care (while understanding that when it’s a character-focused scene, the setting can drop out, since too much information in one panel is distracting). The comic is food-focused, so rendering delicious looking food is also important. The characters have pretty simple faces, except when it’s a character-focused scene, and then we see them rendered in more detail.

Mœbius was a French cartoonist with an interest in surreal fantasy and science fiction. He devoted his energy and time to rendering elaborate backgrounds, to making worlds that pull the reader in. His work is not as interested in making a character or story that you deeply relate to - he has a cool idea, and wants you to bask in the lushness of his art. His books are highly conceptual, but the art style draws on realism enough to make the surreal visuals immediately understandable.

I could go on about this forever but those are just a few examples!

Finding the style for your book

So ask yourself…what are the most important parts of your book? What are you the most interested in conveying as an artist?

When thinking about the characters, ask yourself -

Do you want them to feel aspirational and cool, or deeply relatable?

Do you want the reader to feel like they’re watching the story unfold, or like they are in the story?

Are you telling a dramatic romance, or a comedy, or a realistic, emotionally incisive story, or an action adventure, or an autobiography, etc?

The answers to these will help you figure out your style. This diagram by Scott McCloud from Understanding Comics, below, is a GREAT breakdown of realism vs abstraction (I highly recommend this book). He explores the idea of a spectrum with text on one end, and photorealistic art on the other end. Think about where your comic fits!

When thinking about the world of the story, ask yourself -

Do I want the reader to feel transported to the places I’m drawing?

Do I want them to understand the mechanics of a fantasy or sci-fi world?

Do I want this to look like it’s grounded in reality, even if it’s not our world, or do I want it to feel surreal, like the rules of physics don’t apply here?

Is it an action story? Does the environment need to be a place the character can move through in dynamic action scenes?

Of course, you probably already have an art style, and things that you are interested (and not interested!) in drawing. So you can ask these questions backwards, too - what kind of story does your art style suggest?

Designing

The above should inform what to design for your graphic novel. I’ll talk about page layouts and panels in another post since that is its own giant topic!

My stories are character focused. I tell fantasy stories with magic, but the rules of the magic is always less important than the emotions of the character. The comics are set in beautiful, escapist worlds, but again the characters take narrative priority over the world they’re in. I want my main characters to feel relatable, while still conveying their own personalities. I want my reader to understand and feel the character’s emotions by their faces alone, no words needed.

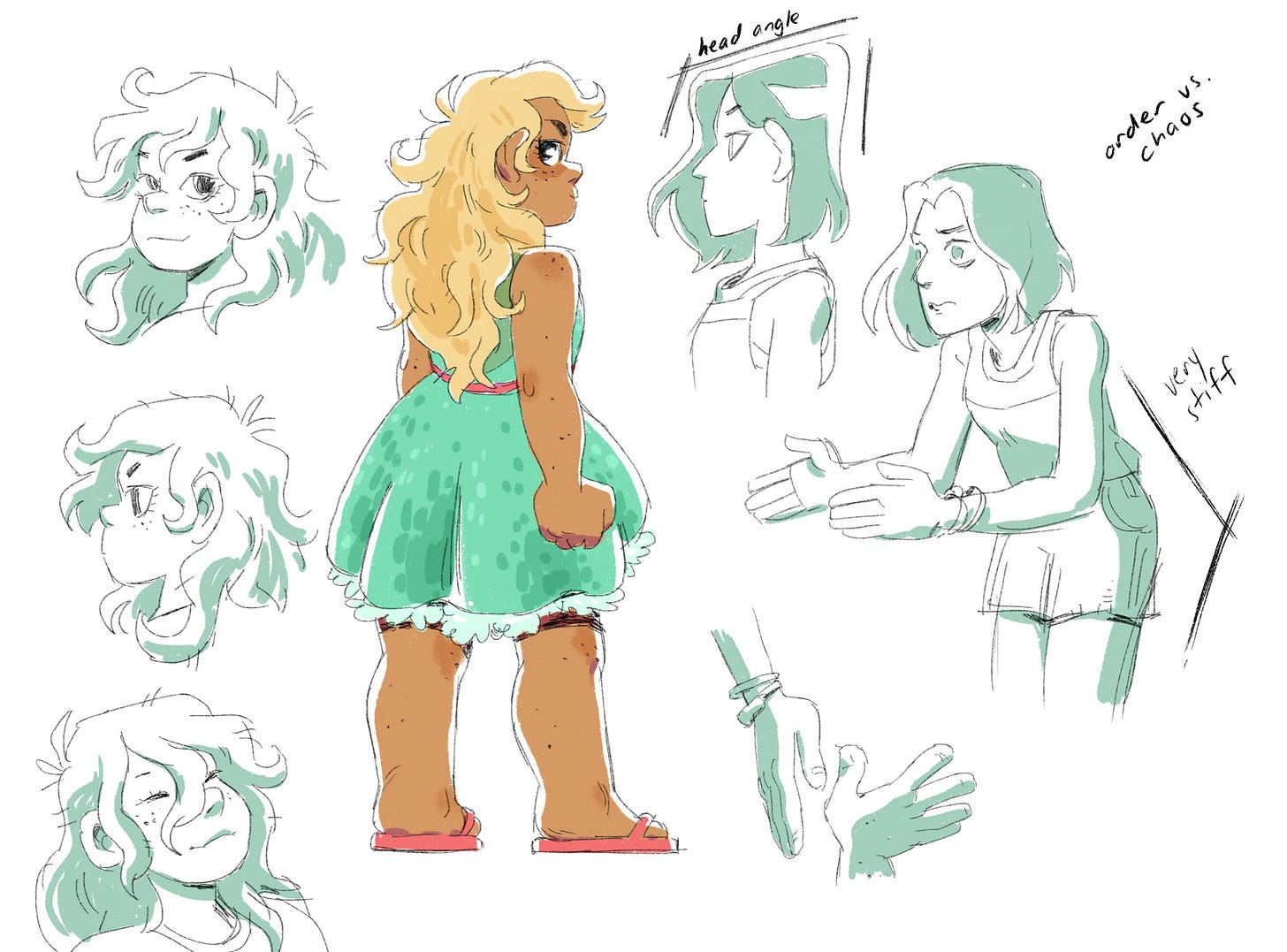

So I always design characters first. Finding the characters visually is a vital part to figuring out stories for me. When I was brainstorming for The Girl From the Sea, I knew I wanted to tell a romance and a story about being closeted. I wasn’t sure what the characters’ personalities would be yet. But as I started drawing them, I found that Morgan - the closeted, socially anxious teen - was rigid and stiff. Keltie - her wild love interest who brings chaos along with romance - is curvy, freckled, with uncontrollable wild hair. The visual difference in these characters went on to be the central dynamic of the book, and it wasn’t something I could have discovered without drawing them.

I let myself draw them a lot, playing with different proportions and faces and fashions. Figuring out how to make them as expressive as possible, because this is a story about feelings. And because it is a romance, their interactions are central to the story, so I drew little moments of them interacting to figure out that dynamic.

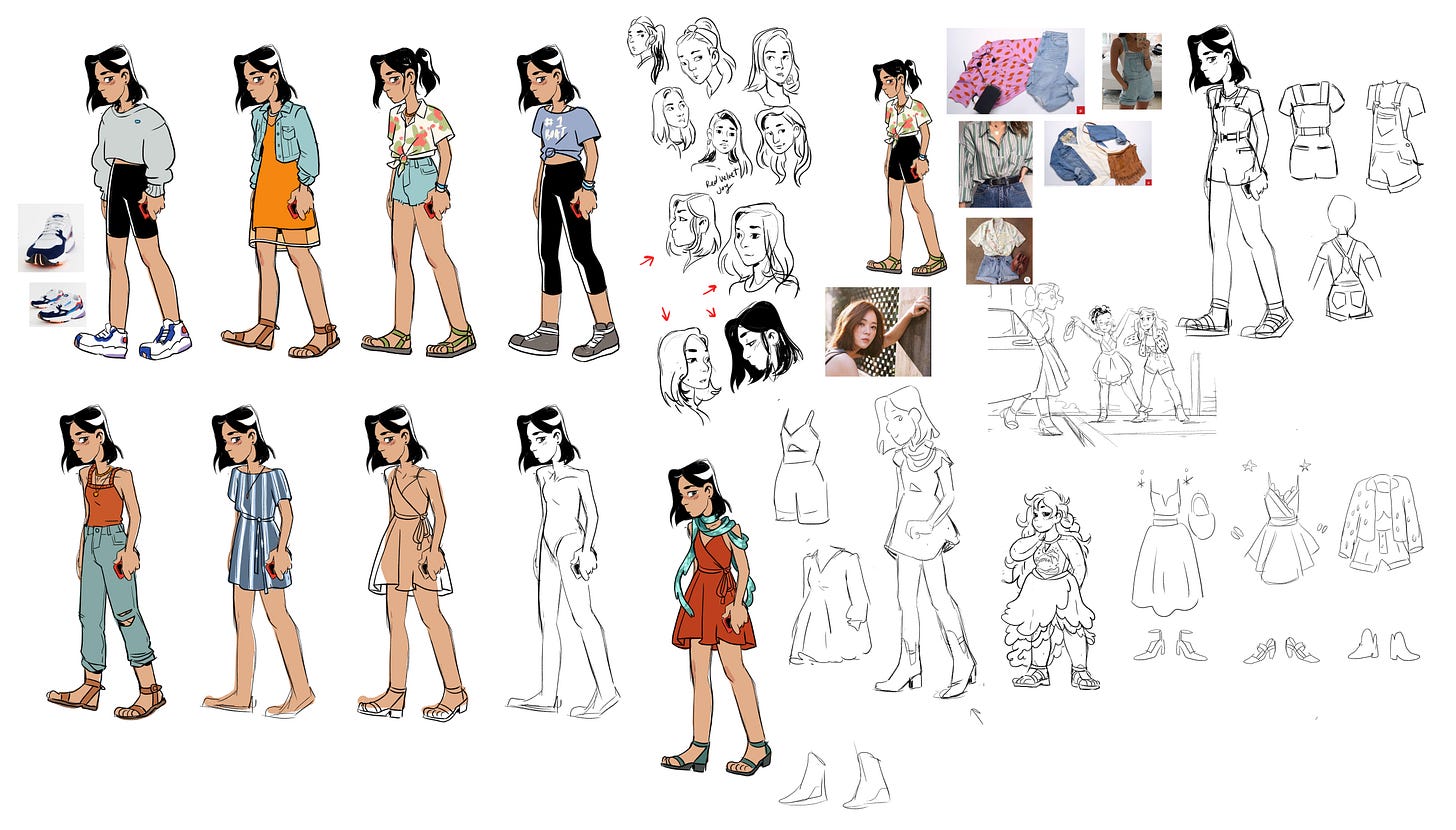

I looked up references, trying to find actors or random Pinterest people who looked like the characters. I also did a deep dive into fashion, since that’s another theme of the book, and another way to express the characters. Morgan is carefully put together; Keltie doesn’t care. I drew a bunch of clothing options for them so that, once I was in drawing-the-book mode, I didn’t have to pause between scenes and switch to design mode. (clothing inspiration from Pinterest, Teen Vogue, and stores like Forever 21 and Shein)

So that’s development art for a teen romance book. Let’s say you’re making a book about giant mechas fighting monsters. You’re really amped to draw these big action scenes, more interested in those scenes than in the people piloting the mechas. That means your development art will, naturally, be more about mechas and monsters. You’ll want to think about how they move, what they can do, and develop designs that will shine in action scenes. Your world should feel real to lend weight to these sci fi concepts, and to be a stage for your dynamic action.

I know that my stories will always come down to human interaction and emotion, so that is what I’ve focused on learning. Knowing what kind of stories you want to tell will guide your artistic development.

Evolving style

I get asked pretty regularly how I maintain a consistent style through my book. And the answer is that I don’t. Here’s a comparison of pages from the beginning and end of The Witch Boy. The difference is noticeable, but you can still recognize the characters, and that’s what matters.

Feeling like you need to have a consistent style can hold you back from starting. I’ve known artists who begin books, and during the first few chapters they have the inevitable jump in skill that always happens when you’re working on a big project. They feel like it’s so obvious that they’ve grown, it’s time to go back and redraw the beginning. Of course, by the time they’ve redrawn chapter one, chapter two ALSO needs to be redrawn, and it ends up becoming an ouroboros of perfectionism.

So, if you need some affirmations: Your style will change as you go, and that is good. You will figure out how to draw the characters more simply. You will become faster and better and discover more of those visual shortcuts I talked about up top. This is always what happens when you work at something - this is learning by doing. But I promise, that change is a thousand times more obvious to you than to anyone else! Resist the urge to go back to the beginning, at *least* until you’ve finished the whole book. There are so many panels and pages that drive me crazy when I flip through any of my books…but on the whole, I’m glad I finished them and put them out in the world, even if I could draw them better now.

Have you ever noticed that a cartoon character will change looks in between seasons of an animated TV show? This is because character models get locked at the beginning of the season - the character is designed and the animators have to stick to that exact design pretty strictly (this changes depending on show style of course). But then a team of artists and animators draw the characters tens of thousands of times. That process naturally discovers all the parts of the design that don’t work as well, are harder to animated, don’t look good from a certain angle, etc - things you can only find out from drawing a character that many times. But! Instead of changing the character model as they go, they can only update it at the start of a new season.

We’re making comics and so there’s a lot more wiggle room (and a lot fewer people working on it; and a lot less money). So don’t hold yourself to a the animation standard of staying on-model. If you need to change something mid-story, go for it.

Finally

As always, this is intended to give you things to think about, NOT hard rules. Contrasting an art style with a narrative style is a choice, and one that can result in really cool work! You can use a Looney-Toons style to tell an emotional story about heartbreak. You can render the suburban landscape of a stoner comedy with all the intricacy of Mœbius’s fantasy worlds. You can draw a mecha story in a scratchy, realistic autobio style. The contrast says something, in and of itself.

Your style does not limit the kind of stories you can tell, but it does inform them. Art style is not neutral - it is as unique as your fingerprint, and exploring it will help you become a better artist and storyteller.

I feel ready. I think. Maybe not. What's the worst that can happen? I liked Scott McClouds book (a friend gave it to me). I'm inspired and feel ready to try. I really liked the idea of expanding your personal style (which I'm still figuring out).

YAY - I can finally convince myself not to redraw some old pages 😂