I’m going to take you through the process of a graphic novel in a series of posts. This is from my perspective, as a writer and artist who makes fantasy books for middle grade and young adult readers - but hopefully it will be helpful even if you’re interested in making a different kind of book!

So! You have an exciting idea. You have an outline. You have ideas for your art style and you’re starting to draw concept designs. It’s time to…

Write the script!

The scripting process is the work of fleshing out every moment within your story. You can be as descriptive as you like in this stage - with your outline as a road map, you can let the script really dig into how you want the scenes to feel, describe little details that feel visually important, and let the conversation between your characters flow.

There are various official formats for scripts. Movie and TV scripts are expected to look a certain way - but truthfully, there’s nothing I love more than writing comic scripts, because I can format them however I want.

I write my comics like novellas. I script without worrying about page count or how I’m going to lay it out on the page - unless I have an exciting idea for a dynamic page spread or a panel, in which case I’ll note it in the script. I usually write in present tense because it feels the most natural to me, you don’t have to. I try my best to describe the pictures in my head, and when I can’t imagine how a certain sequence will look, I’ll at least describe everything that I know has to go there.

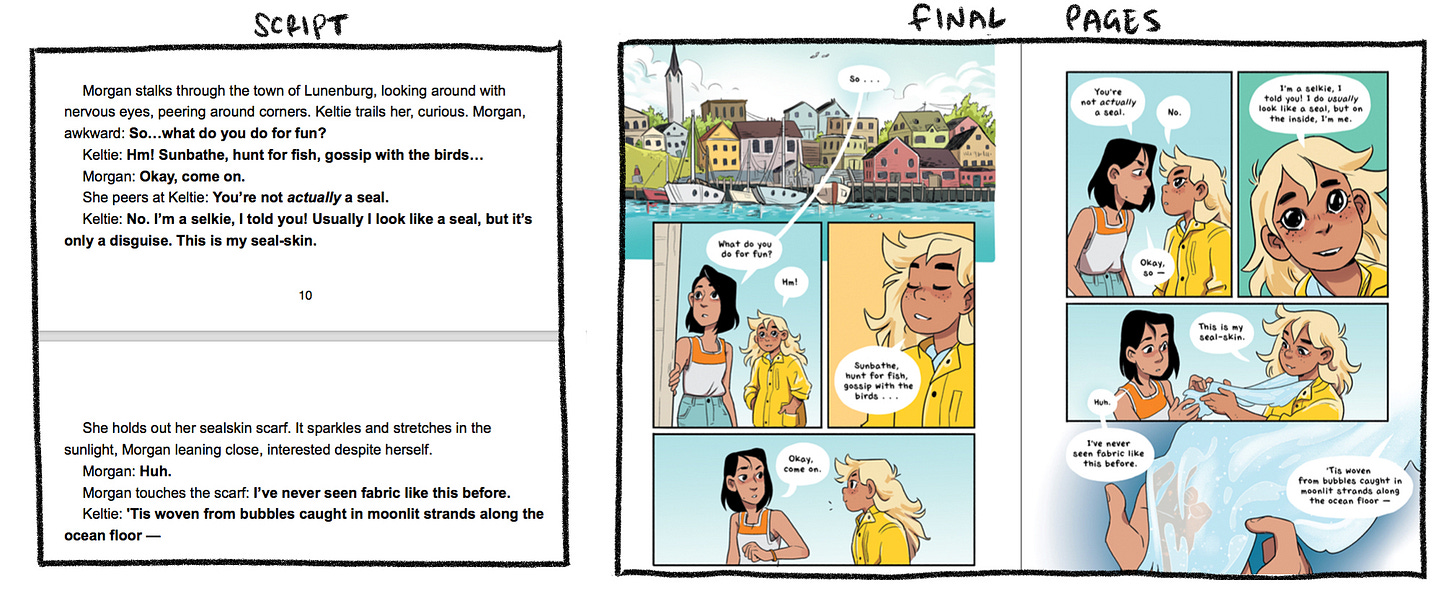

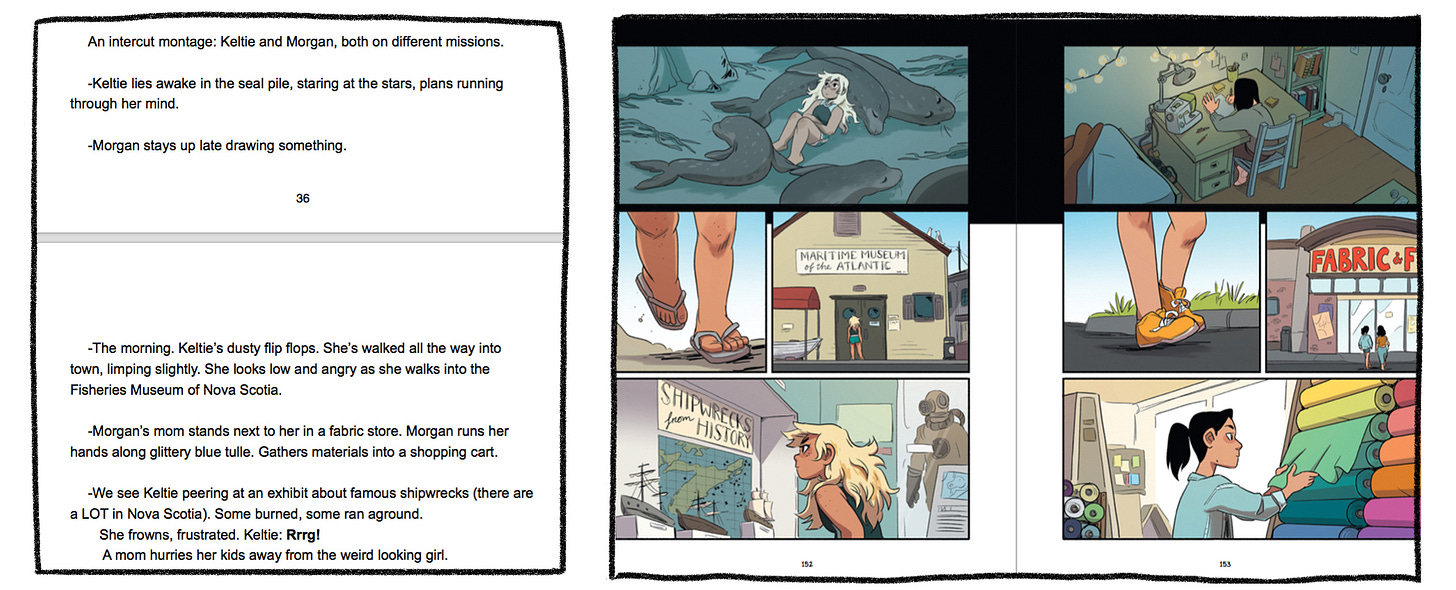

Here are examples of my scripts, and the pages they turn into. Both examples are from The Girl From the Sea - the first is a conversation-oriented page spread, the second a visuals-oriented spread. (A page spread refers to the two pages that lie side-by-side when reading a book, fyi!)

Length and Narrative Space

I will talk about thumbnailing - the process of breaking down a script into page layouts - in a post soon. I write my story without breaking it into pages first, which I know isn’t standard for everyone. Diving into the story without knowing exactly how long it will be can be nerve-wracking. What if you end up with way too much story, or way too little?

In order to make sure my graphic novel scripts don’t end up being too long or too short, I consider how much story can fit in a graphic novel. At this point it’s an instinct, but before I developed that instinct I would literally take my favorite graphic novels and break down how many scenes there were, and how many pages per scene. This is obviously a very rough science, but it gave me an idea of how much story can fit in a graphic novel. The Girl From the Sea has about twenty disparate scenes (I’m counting any significant location change or time jump as a scene change), which is a LOT less than a prose novel of the same genre.

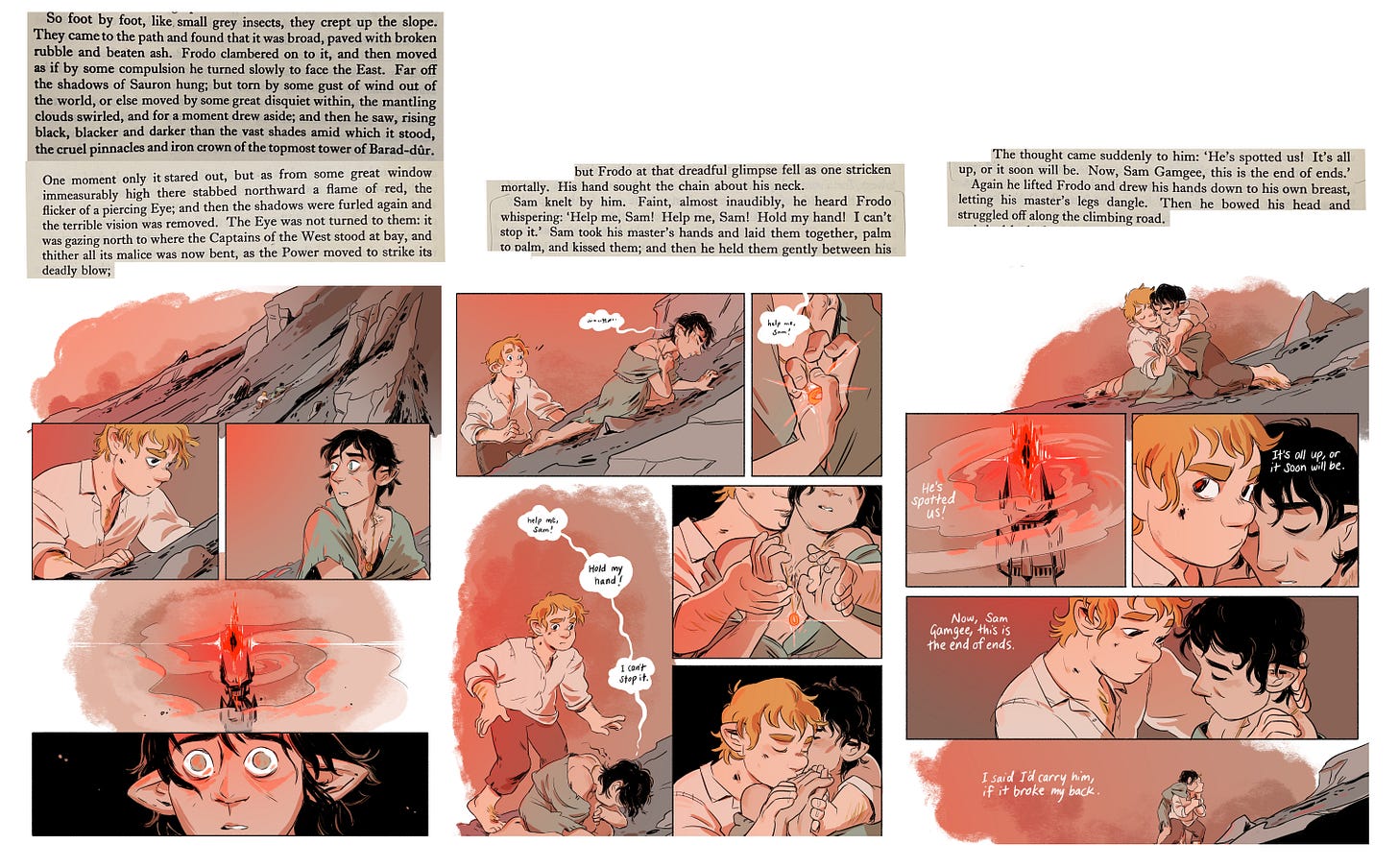

I’ve found that graphic novels have much less narrative space than a prose novel. An example - I do these fan comics based on text from the Lord of the Rings. The one below is based on half a page from the Return of the King. That translates into three comic pages. If I do some clumsy math, then faithfully translating all of Lord of the Rings (1,086 pages) into comics (assuming a rate of 3 comic pages per 1/2 page of prose) would make…a 6,516 page long graphic novel. Which, I think we can all agree, is a bit much even for me.

This doesn’t mean a graphic novel is lesser than prose - it’s just a different medium. You probably can’t include as many separate scenes as a novel can. BUT, the visuals and drawing style, and the combination of words and text, create subtlety and depth in a way that’s wholly unique to comics. Recognize the kinds of stories that work in graphic novels, versus prose, versus film, versus TV. Each medium shines in its own way!

My graphic novel scripts end up being between 10,000 and 15,000 words, so maybe that is helpful figure to know! For me, that translates to 200 - 250 pages of comics.

Dialogue

What I like the most about script writing is figuring out the flow of conversations! I suggest always writing more than you’ll need, because often you’ll find you can cut lines as you get into visuals.

Some people love writing dialogue! If you’re not one of those people, here’s a few tips:

Come into the conversation with a narrative goal. The characters should start in one place and end in a different one - whether they have learned more information, revealed something, agreed to something, had their mind changed, etc. Also be open to this goal changing! Sometimes once my characters get chatting they take it in directions I wasn’t expecting. This is generally a good thing to pay attention to - if you’re having trouble getting your character to say what you want them to, maybe the plot needs changing.

Be aware of where the characters are speaking from - are they upset? Curious? Sleep-deprived? Bored? What just happened to them before this conversation that is shaping their mood? What are they anticipating? How do they feel about the person they’re talking to? What do they want to get from the person, and what do they want to convey? Are they saying one thing but feeling another?

I had a teacher in college suggest going out into the world and writing down strangers’ conversations. This feels a bit invasive to me, but I get the idea. The next time you’re in a group setting or on a group zoom, pay attention to the flow and the way people go back and forth. Even chatty podcasts or reality style TV shows are a good source of this (like the discussion on drawing from life vs drawing from art, you’ll learn more from listening to real conversations rather than scripted conversations). There’s a pattern that emerges, almost a melody, that you’re trying to capture in writing!

Remember that the visuals will add context. Anything that you can show with an expression or body language will add depth to the dialogue. This conversation between Morgan and Keltie (below) would read one way as simple text, but with the added clues of Keltie’s expression in the third and fourth panels, we can see that she’s unhappy with the plan even as she agrees to it.

Finally, I suggest reading dialogue aloud as you go (with the caveat that I am a former drama kid so I find this kind of thing fun). This will help you discover if you’re repeating a word too many times, let you play with alternate phrasing, and help you figure out the most natural flow of conversation.

Narration and Point of View

I was not a fan of narration in comics for a long time. It felt like a shortcut - having a caption that said what the character was thinking, feeling, and seeing, rather than showing it in the art. Then…I decided to write a romance book. My goal with The Girl From the Sea was to make the reader feel like they were in Morgan’s shoes, with all the baggage and anxiety she brings into the story. I wanted them to feel like they were falling in love with Keltie alongside Morgan. And I realized I was totally wrong about narration - it’s a very powerful tool for putting the reader directly in a character’s head.

Point of view is an interesting topic in comics. Your reader is not seeing the world through a character’s eyes in the same way as a first-person prose novel. Even if there is a main character narrating, the reader is still looking at the character and their world in a semi-objective way. In first person prose, the narrator tells you everything you know; in comics, your own eyes give you a lot of information. I just read We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson (prose novel) and loved how the reader knows very little about the identity of the narrator, including her age and appearance, until the end of the story…something that would be really tricky to do in comics. If you want a strong point of view, narration can help achieve it!

I don’t have narration in The Witch Boy series. I wanted them to feel like magical adventures with a group of defined characters who all get to have moments in the spotlight, who all have story arcs. When a story is told from a specific point of view, it can feel strange to show scenes the POV character isn’t present in (when the reader has information the POV character does not, it distances them from the character), and I wanted to be able to jump around. If The Witch Boy books were prose, they would be written in third person.

The Girl From the Sea is a much more internal story. There’s not really a villain outside of Morgan’s anxiety and fear of coming out. The story’s arc focuses on the change happening within her mind and heart, rather than an exterior change in the world. Almost every scene is from her perspective. There’s a few scenes where she’s not present, but they’re rare and even then the characters hold information back from the reader. If The Girl From the Sea was prose it would be written in first person.

My spouse makes autobiographical comics that are often in second person, which is a way to connect directly with the reader and make the comic feel really personal and intimate.

Like everything in your story, it’s a choice! Think about how you want your reader to experience the story when you’re considering whether to give your main character narration, or not.

Description

The other component of a script is description. This varies hugely depending on the project.

I was REALLY descriptive with The Witch Boy script. It was my first book, and I was working with an editor who I wanted to be able to see it as clearly as I did. As I continued to make the series, the description got more and more sparse. I included enough for my editor and any other early readers to be able to understand, but I knew that I would be the one drawing the art, so I didn’t need to get too wordy. Also, I had established the vibe of the story and many of the recurring settings and characters, so I didn’t need to keep describing them.

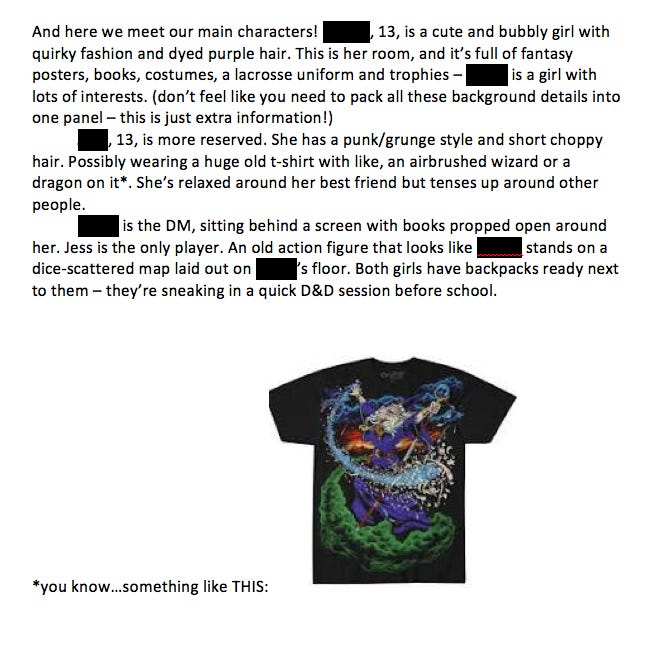

I’m writing a graphic novel for an artist for the first time right now. It’s interesting preparing the script for them - I don’t want to be so descriptive that I slow down their reading, and I don’t want to impose my visual ideas when someone else is going to be drawing them. But I also want to give them material, rather than leaving all the visual research and brainstorming to them. A lot of times I’ll give a list of things in the setting/things about the character, and include the ~vibes~.

I feel okay sharing this scene since it’s from an old draft:

Reference

This is also a good time to talk about reference! Finding visuals will always give you more ideas. I start pulling visual reference as soon as I start on a project. As you’re writing the script, it can be helpful to make a folder of really specific things included in the script. I found SO MANY photos of boats and boat dashboards for The Girl From the Sea. Once you’re in the drawing zone, having a folder to look through for quick reference can keep you on track, rather than having to stop drawing to dive into the depths of Google Images.

This goes for writing if someone else is illustrating! If you aren’t a visual artist at all, it’s still very helpful to share pictures of anything you are specifically imagining.

When is it done?

Writing will always be weird to me, because I started as an artist. If you spend six hours working on a piece of visual art, you will have done six hours worth of work. You will have put down marks on the canvas and made tangible progress - drawn two comics pages, inked an illustration, whatever.

Spending six hours writing is more like…you sit down to write, and if your brain is working right off the bat you get a few ideas on the page. Then you realize you need to research and lose an hour down a Wikipedia hole. Then you spend another hour trying to pick the perfect name for a background character, even though you TELL YOURSELF that you can rename them later you know you never will, and by the end of the hour you’re wondering if you’ve ever heard anyone’s name at all, ever, and isn’t the concept of names kind of bizarre to begin with. Finally your second coffee hits and you ACTUALLY write a whole scene, except for the place where you wrote ‘joke goes here’ that you promise yourself to return to. And inevitably, five hours and forty-five minutes in, you realize that you have a better idea for this scene and you need to scrap all your work for that day.

It’s frustrating! Oh my god is it frustrating! But on days like that, even though it feels like you didn’t make any progress:

YOU DID.

If finding a story is finding your way through a labyrinth, then you just went down a bunch of corridors and found dead ends. Now you know they are dead ends, which is helpful information! But not only that, you found things along the way: a name for a character, a bit of research that expands your view of the story. Days like that are your brain working through the basic ways the story could go, so that you can move on to a better version the next day.

Put a lot of text down - put anything down - even when it’s stupid or scary to write, just put SOMETHING down. Like climbing rungs on a ladder and getting to see more and more of the world around you, the act of writing itself will give you ideas! And then you get to edit out the bad stuff and keep the good stuff! (I am writing this to remind myself because I forget this constantly)

I re-read my work a lot. Usually when I sit down at the start of my work day I’ll re-read everything to orient myself. I find little dialogue tweaks, get ideas about how to make it flow better - every time I re-read, I make changes. When I’m really stuck, I’ll take a few days off and come back with fresh eyes. If you don’t have a few days, a walk or a yoga session or breaking to do chores can help. Talking to someone else can help immensely too - just describing the story out loud will clarify it in your head.

Writing for a visual medium is interesting because the finished script won’t be seen by anyone except you and your editor, maybe agent, people in your writing group, etc. It’s not the final place this story will end up - it’s still a step on the way. Some things that will work in a script won’t work in visuals, and you won’t figure out until you get there. But in order to do a good job, you need to let yourself live in the stage it’s in. Focus on writing a good script while you’re there.

Sensitivity Readers

Script phase is a great time to bring in sensitivity readers. These are people from identities that you are representing in your story, who can read your story for authenticity, check for any stereotypes and tropes, and give suggestions to make characters feel more genuine.

It can be tricky to find a professional reader - a lot of large scale databases have shut down because of trolls. Here’s a database that’s still up. If you’re working with a publisher, they will have their own internal connections, and will usually cover the cost. You can also reach out to people you know and trust.

This webinar is an excellent resource to talk about working with readers. The program in general, Writing the Other, has lots of great, thorough, and informative courses on these topics.

When you’re working with a reader, it can help to have specific questions - “What would someone from a traditional Korean background make for family dinner?” “If a trans guy was starting on T, how would he take it?” “What’s a casual way to refer to a boyfriend in Spanish?”

If you’re worried that something in your piece could be upsetting, I recommend flagging it for the reader up top. And since you’re making a visual piece, ask for photo reference and things to read and watch. If you can, bring the reader back in to look at the art - and definitely show them the character at at script stage. But if you can only work with them for one session, do it with the script. It is infinitely easier to edit text, and it shows that you’re open to them proposing big changes. Collaborating with a reader is a huge privilege and a wonderful resource, so be respectful and thoughtful of their time and work!

That’s it for today! As always, drop questions down below and I’ll try to answer :)

This may be off-topic, but I have been thinking about it since you mentioned you did fanfiction for fun last summer as a way to decompress. Do you do extensive outlines for these fanfictions, like your 73K novel “In All the Ways There Were,” or did you write it as it came to you? Just curious if you use the same creative process across the board, or if there is a difference.

THANK YOU for that accurate description of the 6 hour writing process, oh my god. this often happens to me, going down the wikipedia hole, spending half an hour focusing on a side character's name and writing [joke goes here] so I don't lose the flow when I'm finally getting a scene done. my god, it is frustrating!

I kind of always feel guilty when this happens to me because I have an 8-hour daily job and write on my free time, so when I don't meet my writing goals I end up feeling like I didn't fully seize my time. but thank you for reminding me we all go through that, and most importantly, that writing sessions like those are just a natural part of the process.

again, thank you for this class, I hope you have a fantastic week!